The Translation Process

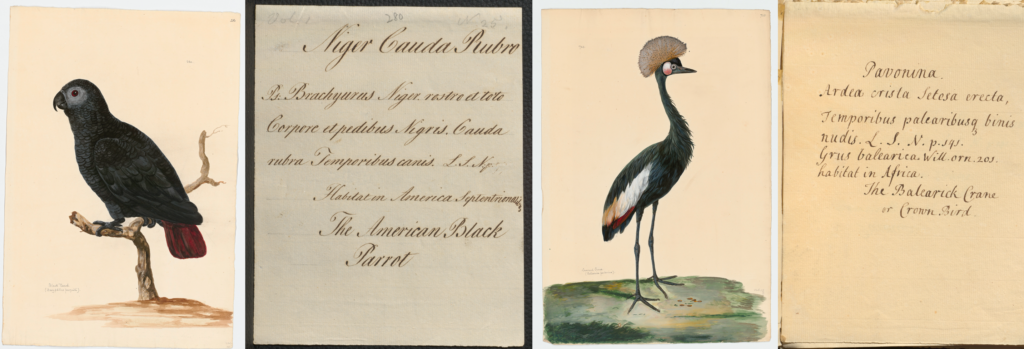

In translating Taylor White’s notes, the goal was to make the text as faithful as possible to the original Latin while also making it available to a modern English audience. As any translator will know, however, this is rarely a straightforward task. Words can have multiple definitions, grammatical structures can change the meaning of a particular word or phrase, and an author could easily have made a mistake while writing. In Latin especially, even changing one letter in a word could change its entire function in the sentence, making the intended meaning much more difficult to discern. Here, then, as with many other translations, I sometimes had to make judgement calls in order to come up with an acceptable translation. Throughout this process I made use of a number of resources, namely a variety of Latin dictionaries (especially Lewis and Short’s A Latin Dictionary), Linnaeus’ Systema Naturae, as well as modern anatomical diagrams, glossaries, and descriptions. Taylor White’s collection of paintings was, of course, also invaluable in providing a visual representation of the animals described in the notes, which could then be compared to the Latin text.

We decided that these translations should be aimed at readers familiar with the conventions of animal descriptions used in modern field guides. When dealing with birds, for example, the reader will find that I used terms such as “semi-palmate” rather than “half-webbed”. At the same time, however, in order to keep the translations as accessible as possible to a general audience, I translated words such as “rachis”, “supercilium”, and “tectrix/tectrices”, (words that do exist in a scientific English context), with their slightly more common forms of “shaft” (of a feather), “eyebrow stripe”, and “covert feathers” respectively.

Another challenge that arose when dealing with scientific terms was the fact that the technical Latin terms Taylor White was using to describe animals in the eighteenth century are not necessarily terms that are still in use today. A prime example of this would be the word “tempus, -oris”, which can literally be translated as the “temple”, i.e. the side of the head near the eye. While this is a perfectly ordinary word in the everyday English language, it no longer seems to be a term one finds in the anatomical description of birds. Unfortunately, however, determining the exact technical word that would best fit the description turned out to be an impossible task. In the paintings of birds associated with the notes in which Taylor White used the word “temple”, the area that seemed to correspond to this word was anywhere from a circular area immediately around the bird’s eye, to the side of the head, and down through the cheek. I considered using terms such as “ear-coverts”, “auriculars”, “orbital-rings”, “eye-rings”, etc., but none of these really seemed quite accurate. Given that Taylor White’s use of “tempus” seemed inconsistent, or perhaps rather, referred to an area of the bird’s head that has since been divided into several different parts in anatomical terms, I kept “temple” in the translations, with the hopes that readers will understand and accept its use in this particular context.

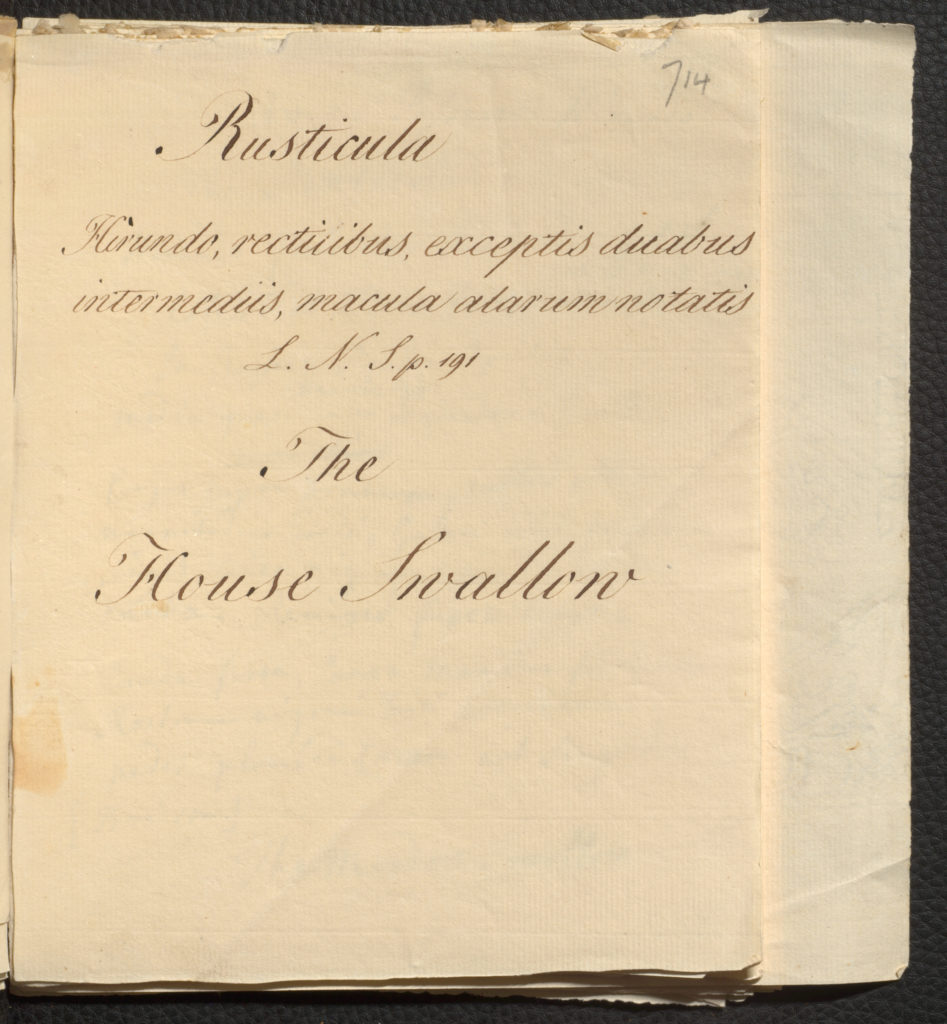

Determining how to translate certain words was thus difficult enough; this became even more of a challenge when words were spelled incorrectly. As many of these notes were hastily written drafts, quite a few errors did find their way into the text. In some cases, these mistakes were fairly easy to identify and correct, with only a letter or two missing or the wrong letter appearing (e.g. “recticibus” instead of “rectricibus”, “cirda” for “circa”, “faciis” for “fasciis”, “vertibus” for “verticibus”, “fulcus” for “fulvus”, etc.). In other cases, however, correcting mistakes was much more challenging. Sometimes the wrong word entirely had been written, and sometimes the grammatical construction just did not quite add up. In notes where White referenced Linnaeus’ Systema Naturae, I could usually solve the problem by comparing the text in the notes with the description of the same animal that had been published in Linnaeus. This technique worked for example, with note #714 describing a house swallow, in which Taylor White’s note included the phrase “macula alarum notatis” (which, literally translated would be “marked with a patch of the wings”, which does not make much sense). In Linnaeus, however, the same phrase was written “macula alba notatis”, which instead means “marked with a white patch”: a much more reasonable phrase! In such cases, then, I assumed that Taylor White did in fact make a mistake and I based my translation on Linnaeus’ text instead.

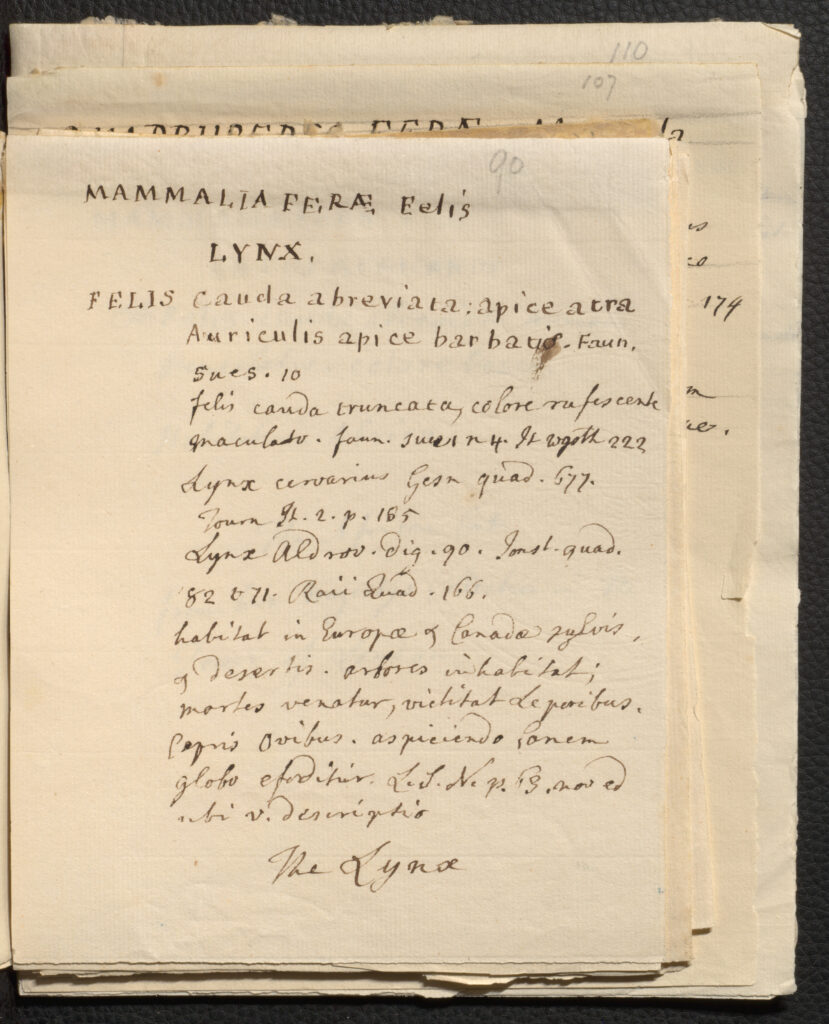

When the description did not appear in Linnaeus, making a comparison impossible, or the grammar was as equally complicated in the published text, a literal translation seemed the best option. One particular example of this can be seen in note #90 describing the lynx, in which Taylor White has written “aspiciendo Canem globo efiditur”. This phrase also appears in Linnaeus as: “aspiciendo Canem globo perfoditur”, but in both cases the grammar was equally difficult to unravel. Some of my early suggestions of possible translations for this sentence included “when [the lynx] sees a dog it turns itself into a ball”, “seeing a dog, [the lynx] strikes through the pack”, and “having seen a dog in a pack, [the lynx] tears it apart”. While some of these make more sense than others, these translations were all so far removed from the original Latin text that it was simply not possible to justify using them. After much deliberation and unfruitful research about lynxes, my best option seemed to be to keep a more literal translation. Thus, the current translation now reads “When it sees a dog in a pack, it is transfixed”. This, unfortunately, is only one of several instances in which I had to use a literal translation, or had to make assumptions in order to make sense of words that simply could not function together grammatically.

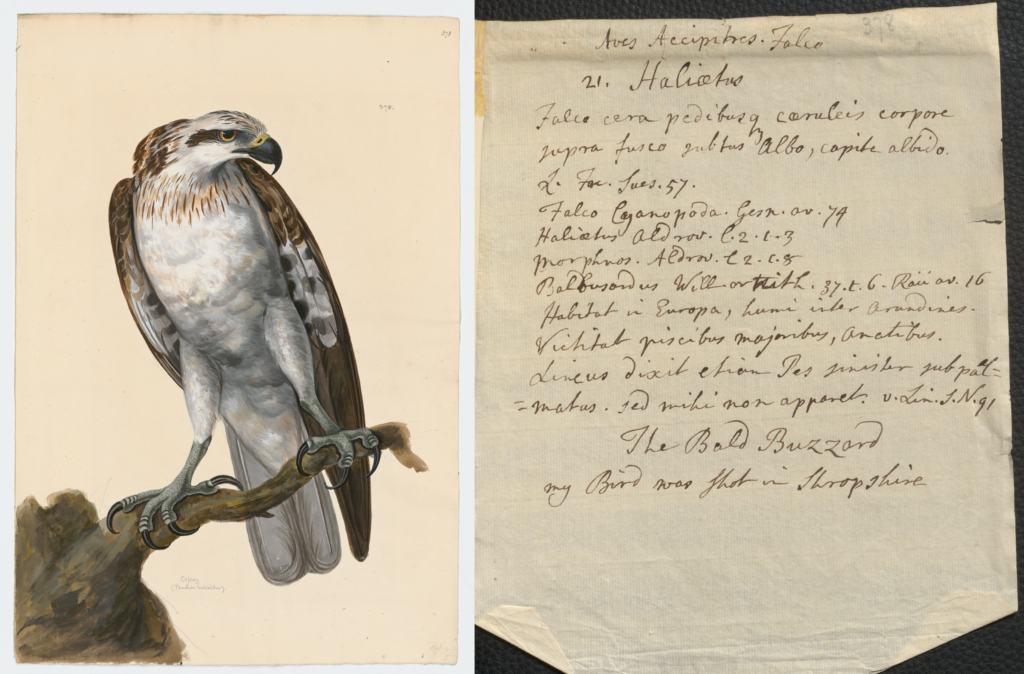

Happily, in some cases, a bit of extra background research did help clarify some seemingly odd Latin phrases and led to some interesting discoveries. One of my favourite examples occurs in note #378 about the osprey (or Bald Buzzard as Taylor White calls it), in which White comments that “Lineus dixit etiam Pes sinister sub palmatus. sed mihi non apparet”, that is “Linnaeus even says that the left foot is somewhat webbed (palmate), but this is not apparent to me”. At first, it seemed as though Taylor White had perhaps made a mistake, that he did not mean only to mention the left foot, or perhaps that “palmatus” here had another meaning besides “webbed/palmate” (it can also mean “shaped like the leaf of a palm tree”). After doing a little more research about this bird, there appears to be a legend originating in the writings of Albertus Magnus in the thirteenth century, in which this bird is described as having one webbed foot and one taloned foot. Making this discovery thus helped me determine the sense of the Latin.

The hope is that these translations can also lead readers to make their own discoveries, or spark their interest to do further research of their own. As a final note, due to the fact that these translations were done in short segments over a fairly long period of time, inconsistencies and inaccuracies inevitably will have crept in. Mea culpa!

Click here to browse high-resolution digital reproductions of the notes mentioned here, as well as others in the Taylor White Collection.

For the specific volumes which include the above notes, see:

Birds Volume 1, Note 280 and its corresponding painting

Birds Volume 3, Note 378 and its corresponding painting

Birds Volume 12, Notes 714 and 723 and the latter’s corresponding painting

Mammals Volume 3, Note 90

–Emilienne Greenfield